Leopold Museum,

Vienna

Vienna

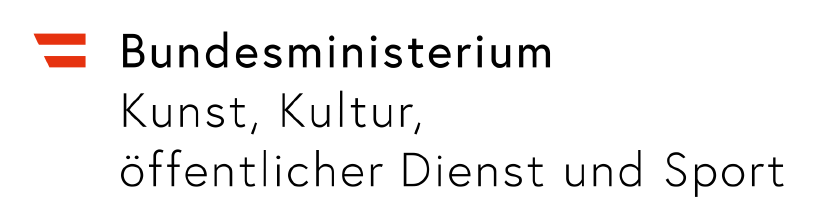

Still Life with Great Crested Grebe

1928

(Bregenz 1893–1939 Bregenz)

If you have further information on this object, please contact us.

For provenance related information, please contact us.

2023/2024 Partial funding for digitization by the Federal Ministry for Arts, Culture, the Civil Service and Sport „Kulturerbe digital“ as part of NextGenerationEU.